Aphrodite is one of the most well recognized goddesses of the Hellenic religion. But where did Aphrodite come from? How did her cult start off? Was she always apart of the Greek beliefs? Why do some authors offer really conflicting origins for her? I’ll intend to provide my theory behind this while going over a lot of history, mythology, and attempts to reconcile it all.

Who Is Aphrodite?

Aphrodite is the Greek goddess of love. She is also the goddess of beauty, sex, passion, lust, and pleasure. Aphrodite, from the period of Archaic Greece (starting in 800 BC) and going onward, is worshiped throughout the Hellenic world as one of the Olympian Gods.

Aphrodite is involved in quite a few myths, especially some big ones.

What Is Aphrodite’s Role In Mythology?

Well, Aphrodite is usually seen doing her job and playing matchmaker. She, and usually with the help of her son, Eros, are seen throughout mythology going around and spreading love to others.

However, Aphrodite’s wrath is also a feature used sometimes in mythology. When she is disrespected, she can quite thoroughly punish someone in usually life ruining ways.

However, going off of that point about matchmaking, there is one very important thing Aphrodite did that involved this subject. The event that set the stage for the Trojan War.

Eris, the goddess of strife and discord, felt snubbed because she was not invited to the marriage of Peleus and Thetis–the parents of Achilles–like the other goddesses were. So Eris took a golden apple, quite the coveted object in mythology, and wrote “To the Fairest One” upon it and then tossed it into a gathering of Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite.

Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite got into a disagreement over who the apple should belong to and the disagreement became so intense that it eventually reached Zeus–who really did not want any of that. So Zeus got Paris, a prince of Troy, to be the judge and select which goddess was the fairest.

Hera offered Paris great political power, Athena offered Paris incredible wisdom and might, and Aphrodite offered Paris the love of the most beautiful woman in the world. Paris ended up choosing Aphrodite, and so Aphrodite made it that Helen of Troy and Paris would fall in love.

Now you might be thinking, what’s the problem with this? Aphrodite lived up to her promise, she sure did. It’s just that Helen of Troy was literally already married to the very wrathful king of Sparta, Menelaus, who also happened to be in a treaty with the other Greek city states to all go to war to help each other against any of their enemies.

So, when Paris took Helen of Troy away with him, this drove Menelaus into a rage and called the Greeks to war with Troy to get her back and punish the Trojans for this transgression. Aphrodite does not hold the sole responsibility for the Trojan War, certainly this is true, but she cannot have been oblivious to what she was doing when she gave Helen of Troy’s love to Paris.

Aphrodite’s Absence From Mycenae?

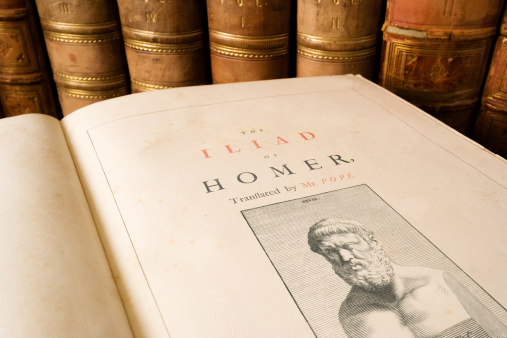

Now what’s really interesting is, the Iliad appears to be the first place that Aphrodite appears in literature. Unlike many of the other major deities of Greek mythology, we have yet to find Aphrodite mentioned at all in Linear B–the language of the Mycenaean people.

The Mycenaean Greeks were the people that controlled Greece from around 1800 BC up until the Bronze Age Collapse, with the most prominent period of their era lasting from around 1600 BC until 1200 BC. The Mycenaean people spoke their own dialect of Greek or at least some kind of proto-Greek language, but they wrote in Linear B which is in syllabic script like Linear A which was used by the neighboring Minoan culture on the island of Crete.

Throughout Linear B, we cannot find any clear reference to Aphrodite among the gods. This means that Aphrodite’s cult had either not begun in the Greek world yet or that she was just too obscure of a deity in that era and did not become prominent until later on.

However, by the time Homer writes the Iliad in the 700s BC for Aphrodite’s first literary appearance, Aphrodite does not just appear as some newcomer. She’s prominent, she’s well known and worshiped, and she’s one of the twelve Olympians.

This shows us that at some point during the Greek Dark Age, which took place roughly between 1200 BC and 800 BC. The Greek Dark Age saw the period of transition from the Mycenaean Era of Greece to the Archaic Era of Greece, but was largely silent in the literary world.

To make sense of the fact that Aphrodite does not appear in the Mycenaean Era of Greece but is already prominent by the time of the Archaic Era of Greece, then it makes sense to assume her worship and her following sprung up and spread out during this Dark Age period.

Well how did that happen? We largely do not know anything for certain, but here’s a theory from the Near East.

Astarte From The East

Scholars have theorized that the cult of Aphrodite may have sprung up in the Hellenic world from the introduction it had to the cult of Astarte. But who is Astarte? Is there any merit to such an idea?

Astarte is the Near Eastern Goddess of love, war, hunting, sexuality, healing, and possibly even fertility. Astarte held great popularity throughout Phoenicia and the entire land of Canaan, however she also had a presence in Egypt as well.

Astarte’s first known appearance comes around 1450 BC in the Ugaritic Cycle. From there, she continued to grow more prominently as a deity worshiped throughout the Near East and appear in other texts of which we mostly just have fragments of or have lost.

So how could the cult of Astarte possibly led to the cult of Aphrodite? Well, the Phoenicians loved exporting her to everyone everywhere they went.

Starting in the late Bronze Age, and continuing even despite the Bronze Age Collapse, the Phoenicians loved seafaring. With their love of seafaring also came a love of trade, and to trade you need to have trading posts.

The pursuit for trading posts led to entire colonies being made by Phoenicia, something that Greece would actually join them in. The two civilizations were contemporaries in spreading their exports AND their ideas across the Mediterranean Sea.

Well, at some point in the rather early phase of their colonizing days, Phoenicia setup a trade colony on the island of Kythera (also spelled Kythira, Kithira, or Cythera). This was the first major place we can see where Greeks and Phoenicians began their interactions, and we know from all the documentation and evidence that we do have that the exchange of ideas between these two groups was massive.

The period by which Phoenicia held its colony in Kythera would have been after the rise of Astarte as a prominent deity to them but before the end of the Mycenaean civilization. This forms a bit of a temporary rift between how Kythera develops and how the rest of the Hellenic world develops.

Among many ideas and innovations, we know the cult of Astarte was brought to Kythira during this colonial period–but largely fell out of practice for the cult that would become something Kythira was much more prominently known for once the Phoenicians were gone: the cult of Aphrodite–of which Kythira was one of the main homes of.

Now it’s important to note here that Aphrodite and Astarte are two different deities and their cults are two different things. The cult of Astarte does not stop existing just because of the rise of Aphrodite’s cult.

And just because the origin of Aphrodite’s cult may trace a possible inspiration back to the cult of Astarte does not mean that Aphrodite lacks any purely Hellenic statuses or myths. She is not a copy of Astarte. Their roles as goddesses may be similar and their cults may be related, but these two deities came from two distinct pantheons and were able to coexist in the ancient world at the same time.

Ishtar From The Even Further East

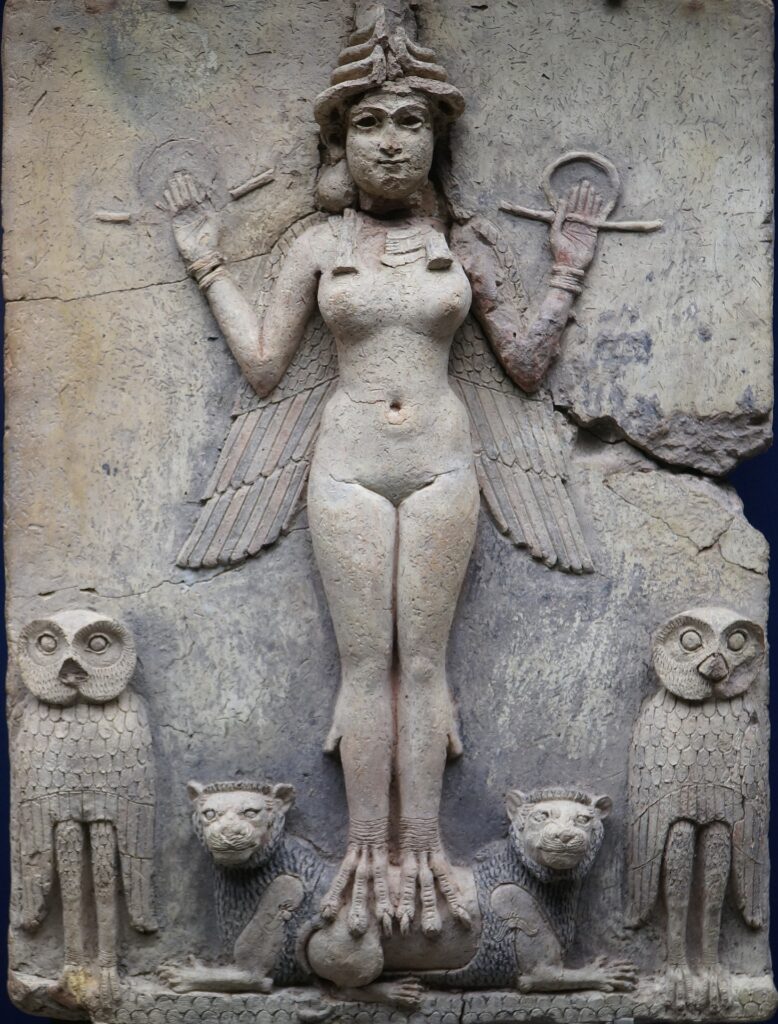

So the cult of Aphrodite may find a possible root in the Greek introduction to the cult of Astarte, but did you know that Astarte herself is also closely related to another goddess? In order to take this scholarly theory as far back as possible, we have to address Ishtar and the history surrounding her and her following.

Ishtar is a deity that belongs to the Mesopotamian religions (Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, and Babylonian) and has a history going back as far as 4000 BC which is over 6,000 years ago. That’s a pretty long time back in human history.

However, Ishtar was not incredibly prominent until after 2300 BC when she began appearing much more in literature in Mesopotamia. Ishtar was held exceptionally highly by the Assyrians and the Babylonians, and her cult thrived across the Middle East for the next 3,000 years until the rise of Christianity.

Over time, it seems that Ishtar’s cult began to move east from Mesopotamia to the Levant where it began to interact with the Canaanite cultures. From archaeological evidence, it seems that, prior to the rise of Astarte, Ishtar even had a heavy impact on the city of Ugarit–which would write the Ugaritic Cycle that Astarte is first known to appear within.

Ishtar is a goddess of sex, love, and war much like Astarte (and like Aphrodite on the sex and love part, also on the war part but we’ll talk about that later), however Ishtar also has greater roles as well–being responsible for justice and politics themselves: a literal representation of power over mankind. Ishtar is even known as the Queen of Heaven in the faith.

To add onto the connections, we also know that Ishtar and Aphrodite have similar myths between the two of them. For example, in one of Ishtar’s myths she gets into a battle with Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Underworld in Mesopotamian mythology, over her husband Tammuz–who was dead at the time and in the Underworld. Aphrodite, in turn, has a myth involving herself getting into a battle with Persephone, the Queen of the Underworld in Greek mythology, over Adonis who Aphrodite was in love with but Persephone had raised.

While these myths, when fully explored, have elements to them that are definitely unique to each of the respective religions they came from, there is one thing that really stands out. Adonis does not simply fill the role of Tammuz, Adonis is Tammuz.

The ancient Greeks identified Adonis as Adonai, who they saw as the national god in Canaan, with Adonai being a name of Tammuz for that area. This builds an interestingly strong undercurrent for Aphrodite to the Ishtar and Astarte line of thought.

However, once again I am going to reiterate the same thing I said under Astarte. Aphrodite, Astarte, and Ishtar are three different deities. They each may serve similar roles and have similar mythologies and their cults may have an identifiable relation, but all three of these deities were still able to develop, be worshiped, and have thriving followings independent and in coexistence with each other.

Aphrodite In Sparta

Now that we have covered where Aphrodite’s cult seems to have possibly originated from, we need to talk about what actually happened with her cult in Greece. To do that, we should address the history of Kythera and its integration into Sparta.

So at some point after the Phoenicians stopped being prominent there, Kythera was brought back into the Greek world when it became one with the Spartan civilization to the north. The Spartans absorbed from Kythera much of what Kythera had imported from the Phoenicians.

Thanks to the merging of Sparta and Kythera, the cult of Aphrodite became popular all across Laconia, the region that Sparta and Kythera can be found. However, this Aphrodite was seen much differently by comparison to the Aphrodite that Homer would write about in the Iliad… this is Aphrodite Areia (Aphrodite the Warlike).

Aphrodite Areia is an epithet given to her by her cult in Sparta and she was depicted as having those same warlike qualities that Ishtar and Astarte are found very prominently with that Archaic Greek Aphrodite seemingly lacks. This is because, according to what we can tell from some political history, the rest of Greece saw this depiction of a feminine love goddess as being a ruthless warrior as rather controversial.

Thus, it seems that during the Greek Dark Ages–when the worship of Aphrodite was being exported outside of Laconia and to the rest of Greece–that Aphrodite was softened from the image of Aphrodite Areia. In the Iliad, Aphrodite is shown to be not very capable on the battlefield itself and is wounded by Diomedes while he is being aided by Athena. After Aphrodite is wounded, she is talked down to by Zeus who reminds her that she apparently has no place on the battlefield and is not a war goddess like Athena.

Even despite this attempt to soften Aphrodite, there is one rather crucial detail that still made Aphrodite very relevant to war in the Iliad. The fact that, as we already talked about, she played a large role in starting the events of the Trojan War to begin with. So, like it or not Ionians, love is a factor in war.

Homer versus Hesiod, or What Origin Of Aphrodite Is True?

In the actual mythology itself, there are conflicting origins as to how exactly Aphrodite was born. This is not necessarily uncommon, but the two methods differ so drastically and Aphrodite is such a prominent deity–therefore it has taken up a fair amount of discussion in the generations that followed Homer and Hesiod (who were contemporaries of each other).

According to Homer’s Iliad, Aphrodite is the daughter of Zeus and a goddess by the name of Dione. Dione actually appears within the Iliad and tends to Aphrodite after she is injured, as well as being mentioned in a few other later myths–though she is not much of a prominent deity in Greek mythology.

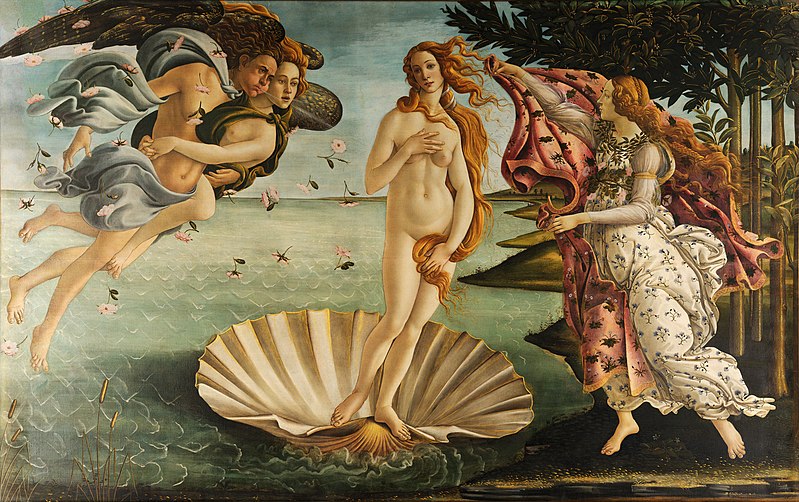

However, Hesiod’s Theogony offers a different origin that has also become the more popular origin of Aphrodite. Hesiod says that Aphrodite was born as a result of the castration of Uranus.

To explain: Uranus was the original king of the cosmos during the generation of the primordial gods alongside his wife, Gaea. Uranus is the literal sky and Gaea is the literal Earth. The two of them had several sets of children, with the first twelve being the Titans.

Due to Uranus’s cruel methods of ruling and his mistreatment of some of their children, Gaea conspired with several of the male Titans to have him overthrown. And so, the Titan Cronus took the lead and, joined by four of his brothers, subdued, castrated, and overthrew their father making Cronus and his sister/wife Rhea the new king and queen of the cosmos.

As a sign of disrespect to Oceanus, Cronus’s only brother that did not join in the rebellion, Cronus tossed Uranus’s castrated genitalia into the waters–Oceanus’s domain. There, the blood of Uranus mixed with the water to create seafoam that would eventually produce a seashell. The seashell would travel to the shore of Kythera (or Cyprus in some versions) and open to reveal the full grown Aphrodite–ready to be worshiped and join the ranks of the Olympian Gods.

So who, if possible to know, among these two poets, is more correct about the origin of Aphrodite? Well, that’s the thing, in a way they are both right.

Remember how we mentioned Astarte and Ishtar earlier when talking about the possible historical roots behind Aphrodite’s emergence as a cult in Greece? Well, Astarte and Ishtar have origin myths that are similar to each of Aphrodite’s origin myths respectively.

Covering the Ishtar one first, in the Hittite religion they had Ishtar be born from the castration of the god Anu by the god Kumarbi–very familiar to the castration of Uranus by Cronus, and those are not the only similarities these two pairs of deities share with one another.

The story goes that when Kumarbi overthrew Anu he castrated him and then ate his genitalia which caused him to become pregnant and give birth to Ishtar. That’s definitely a bit more unique and graphic than the story between Uranus and Cronus, but the similarity is still there.

Next to cover Astarte, this is not really so much of a myth more as it is an explanation, so I am sorry if I misled you earlier. According to Sanchuniathon, one of our main experts from the ancient world on Phoenicians and the Phoenician religion, Dione is either the mother of Astarte, sister of Astarte, or literally Astarte herself.

This is evidenced by the fact that Dione itself is not much of a unique name and rather merely the feminine form of Zeus’s name and that Dione herself is related somewhat to Canaan by the Greeks–kind of like the Adonis and Tammuz situation. It also helps that Dione is not much of a prominent figure in Greek mythology outside of her brief appearance in the Iliad and that every other author seems to have very little and nothing consistent to say about her–if anything at all.

So, wait, how could Dione be Astarte–putting her in the role of Aphrodite–but also be the mother of Aphrodite by Zeus in the Iliad? This presents the theory of two Aphrodites, which I will address soon, but before we get there let’s wrap up Homer and Hesiod.

As we can see, Homer and Hesiod both draw on traditions more ancient than themselves and establish origin myths for Aphrodite that relate back to two other goddesses the origin of her cult seems to be related to. In this manner, we can actually argue that they are both right in a way.

But how can we actually reconcile Aphrodite having two origin stories? Is there any way to make sense of all of this using what we know? Believe it or not, the ancient Greeks of Classical Greece (from about 510 BC until 323 BC) recognized and dealt with these same questions.

Philosophers Attempt To Reconcile Aphrodite

Of the ancient Greek philosophers, four of them would touch on the broad questions surrounding the concept of love and also touch on the subject of Aphrodite and how to deal with her two origins. Those four philosophers are Socrates, his two students: Plato and Xenophon, and Plato’s student Aristotle.

Socrates never wrote anything down, but Plato and Xenophon both write down Socrates’s opinion along with their own–so we can get an idea of it from there. Aristotle has his own opinion, but Aristotle deals more with forms of love rather than Aphrodite so we will not go too deep into that.

In the Symposium by Plato, Plato details a theory of two Aphrodites. Aphrodite Urania and Aphrodite Pandemos. Plato says that Aphrodite Urania is the Aphrodite that was born from the castration of Uranus and is the representative of celestial and heavenly love while Aphrodite Pandemos is the Aphrodite that was born from Zeus and Dione and is the representative of the carnal love that exists among all living things.

In the Symposium by Xenophon, Xenophon repeats this theory but actually disagrees with it. Xenophon argues that these are both epithets of Aphrodite, yes, but that they do not distinguish two Aphrodites but rather two different aspects of the same Aphrodite.

Though both of these are just theories given by these philosophers, these ideas caught on with the people and we see Aphrodite Pandemos becoming very popular in worship and especially to the Romans–who will be addressed next.

I would now like to take a brief moment to propose my own theory based off of what we have learned so far. This is not something I am pulling from any inspiration besides what we have read thus far. Believe it if you would like to.

Knowing what we know about the seemingly conflicting origins of Aphrodite among Homer and Hesiod and acknowledging the theories that these philosophers present as ways to reconcile this conflict, as well as knowing the root potentials of the cult of Aphrodite, I present the following idea. What if Dione is Aphrodite Urania?

Consider that Dione stays among the Heavens and that her name is simply a feminine version of Zeus’s name. Consider Dione’s relationship to Astarte and Canaan. Consider the role Ishtar plays as queen of the gods in relation to the role of Dione and her etymological relationship with Zeus.

Consider all of that, and I present to you the theory that Aphrodite Pandemos is the daughter of Aphrodite Urania (in the form of Dione) by Zeus. This is a connection I have made based on the evidence of everything we have learned and gone over together, and I thank you for indulging it or at least indulging reading it.

Venus

Now that we have covered the role, the cult, the myths, the philosophers, and epithets, let’s take a look at Rome. In Rome, there is a goddess named Venus who is equated with Aphrodite by the Romans. However, this was not always the case.

Initially, in the early stage of the Roman religion and Roman mythology, Venus is a goddess of spring and fertility. She is identified with the planet we call Venus (which, by the way, Aphrodite, Astarte, and Ishtar also are) and also sort of *loosely* identified with love.

Everything changes from around 500 to 200 BC when the Roman religion takes on a much more Hellenized tone. Venus becomes Venus Genetrix, the mother of all Romans.

Venus is the mother of Aeneas with Anchises, and Aeneas is a Trojan hero that eventually founds the city of Lavinium (which leads to Rome later on) on the Italian peninsula after the Trojan War. The Greeks also agree that Aphrodite is the mother of Aeneas in their own writings, she tries to save Aeneas for that exact reason in the Iliad.

Venus receives all of the characteristics of both Aphrodite Pandemos and Homer’s Ionian Aphrodite through these factors as the Romans are now directly identifying her as their mother and as Aphrodite. But there is one unique change, Venus actually regains a trait that is not seen in these roles since Ishtar: heavy relation to political power.

Many Roman emperors and other various politicians were devoted to Venus and this was common throughout Roman history. Julius Caesar was famously among these people, as he traced his line back to Aeneas and in turn Venus as well.

The treatment of Aphrodite as Venus by the Romans is very interesting but it actually causes something to happen back in Greece as well once it is fully conquered and integrated into the Roman civilization. A rebirth of the cult with new aspects.

Aphrodite’s Cult Reborn

Post-Roman influence upon her, the Greeks back home see a rebirth of the entire cult of Aphrodite across the Greek peninsula. Aphrodite once again becomes very popular and prominent to them, but she is different now.

The now post-Roman Aphrodite carries over the traits of representing political power that the Romans associated with Venus as well as the emphasis on the Aphrodite Pandemos side of her. However, she also now has another trait resurface: her status as a war goddess! Aphrodite is once again associated with military power and war again, undoing all of the softening the Ionians had done to Aphrodite Areia before properly adopting her.

For some time, everything had come full circle. This reborn and re-energized cult of Aphrodite would flourish in Greece while Venus flourished in Rome until the eventual rise of Christianity during the late Roman and early Byzantine periods of history.

There would be some rather strange attempts later on by early medieval Christians to associate and reconcile Aphrodite Urania and her imagery with the Virgin Mary, but this was something that did not stick popularly or conceptually.

Pingback: Who Is Hesiod? – Esoteric History

Pingback: Who Is Ares? - Esoteric History